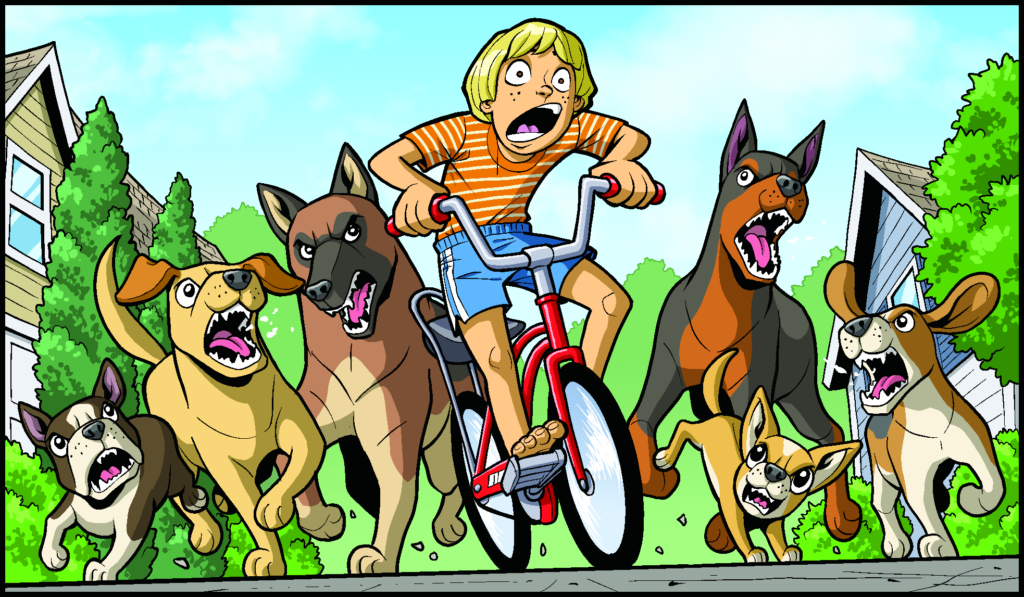

By Matthew Dicks / Illustrated By Sean Wang

It’s a hot summer day. Sun is high in the sky. I’m pedaling up Federal Street in the direction of my home. It’s a serious hill. My legs are on fire, and I can barely catch my breath, but I can’t dare to slow down. My life depends on it.

I’m telling this story to my kids as we scour the garage for everything we’ll need for our journey. It’s early summer, so the bikes have somehow migrated to the back of the garage behind sleds and shovels. After wrestling them free and dusting them off, the real search begins.

A few minutes later, the helmets are found…underneath the lawn furniture. Polycarbonate outer shell with an expanded polystyrene foam interior. A visor to shade the face from the sun and rain. A ventilation system that allows air to flow through the helmet, keeping the head cool and comfortable. And a multi-directional impact protection is designed to reduce rotational forces on the head in a crash. All designed in an aerodynamic package to allow for greater speed.

When I was biking up Federal Street on that fateful summer day many years ago, my head was also protected: loosely woven polyester emblazoned with an interlocking NY affixed to my head with two plastic straps connected by a tiny plastic nubbin.

When I was growing up, no one wore a helmet while biking. Helmet laws didn’t exist until 1987, and it took more than a decade for them to spread nationwide. If my friends and I had seen a kid wearing a bike helmet while growing up, we would’ve thrown rocks at the helmet to test its integrity and let the wearer know how we felt about his stupid headgear.

It was undoubtedly a more dangerous time but also a lot simpler. No digging through the garage to find the helmets. No monitoring of the 3-year expiration date on the average bike helmet. No concern for fit or color or style.

No police officers stopping you on the street for failure to properly protect your melon. No potential DCF calls by neighbors for allowing your children to ride circles in your driveway without helmets.

Just hop on the bike and go, skull unprotected in the event noggin collided with pavement.

Don’t get me wrong. I want my kids to wear their bike helmets.

But I also wish they didn’t need to.

Sadly, though, our preparations are not complete. Once the bikes and helmets have been dragged onto the driveway, the real work begins.

First, we affix water bottles to the frames of the bikes. And yes, hydration is important, but somehow, when I was a child, it wasn’t. I never owned a water bottle as a child. No one owned a water bottle. Water wasn’t sold in stores because what brain-damaged kid would opt for water over Mello Yello or a Mountain Dew? Schools were equipped with a single, white, desiccating water fountain in the corner of the gym. Rumor was that it once worked, but that was long ago.

But it was also fine. We were almost never thirsty. And if it happened to be 100 degrees and we were breaking rocks for fun, we would drink from hoses, faucets and streams.

Yes, as a child, I scooped water into my hands from guggling streams to quench my thirst. I tell this to my kids, and they wretch. They can’t believe it. Part of me prays for a zombie apocalypse just so I can teach my children what it’s like to live in a cushion-less world.

Sadly, the undead do not rise from their graves, so I strap liter-sized water bottles to their bikes. They should last about 9 minutes each before they need refilling.

If I were the kind of parent who can’t imagine their child existing in the world without everything that everyone else owns—and those parents abound like dandelions these days—the bikes would also be equipped with GPS units, first aid kits, tire repair kits, gluten-free seaweed crackers, tracking systems and Go-Pro cameras affixed to the handlebars to record every boring moment of every law-abiding ride.

Add to this florescent clothing, even though it’s not yet noon, and knee and elbow pads. Even goggles are possible.

None of this for my children, of course. I may be providing my kids with unnecessary water, but I haven’t yet lost my mind completely.

My kids and I straddle our bikes and prepare to ride, which is also unusual. These days, families often drive their bikes to locations to ride rather than riding on the roads and paths around their own homes. Biking has become a destination activity, even though a bike is theoretically a means to a destination.

As a kid, I rode my bike everywhere. The basketball courts. Friends’ homes. K-Mart. The library. I rode my bike in the rain and snow. No parent ever drove my bike to a place to ride. I rode my bike to that place.

“So what was the life-or-death situation on Federal Street?” my son asks as we prepare to ride. “Why did you need to pedal so hard?”

“Dogs,” I say.

I grew up in a time and place of unleashed dogs, and some of them wanted to kill you. They would chase you down as you rode past their house, trying to bite your legs, pull you from your bike and tear you to pieces.

As a kid, you always knew the houses with the deadly dogs. On Federal Street, it was the Alders and the Savoys. On Summer Street, it was the yellow house with the two-car garage. Farm Street was a veritable gauntlet of angry canines. Everywhere I rode, the threat of an angry dog was present.

“Dogs,” I tell my son. “Unleashed, angry, dangerous dogs.”

It sounds impossible by today’s standards, but back then, not that long ago, kids were routinely threatened with maiming and death by wild, angry dogs.

My son stares at me in disbelief. Then he smiles and says, “I still think drinking from a hose sounds worse.”

I begin to pedal and pray for the zombies.

Matthew Dicks is an elementary school teacher, bestselling novelist and a record 55-time Moth Story SLAM champion. His latest books are Twenty-one Truths About Love and The Other Mother.

Sean Wang, an MIT architecture graduate, is author of the sci-fi graphic novel series, Runners. Learn more at seanwang.com.

More Stories

Golf Is Never a Swing and Miss

Gayle King speaks to Dennis House

A Horse Is a Horse and More of Course