By Randy B. Young

In his poem, “Reflections on a Gift of Watermelon Pickle,” John Tobias mourns for that summer from his youth, “when unicorns were still possible.” He is heartened that Felicity has preserved that distillation of summer in a jar of watermelon pickle and, “when we slice off a piece and let it linger on our tongue, unicorns become possible again.”

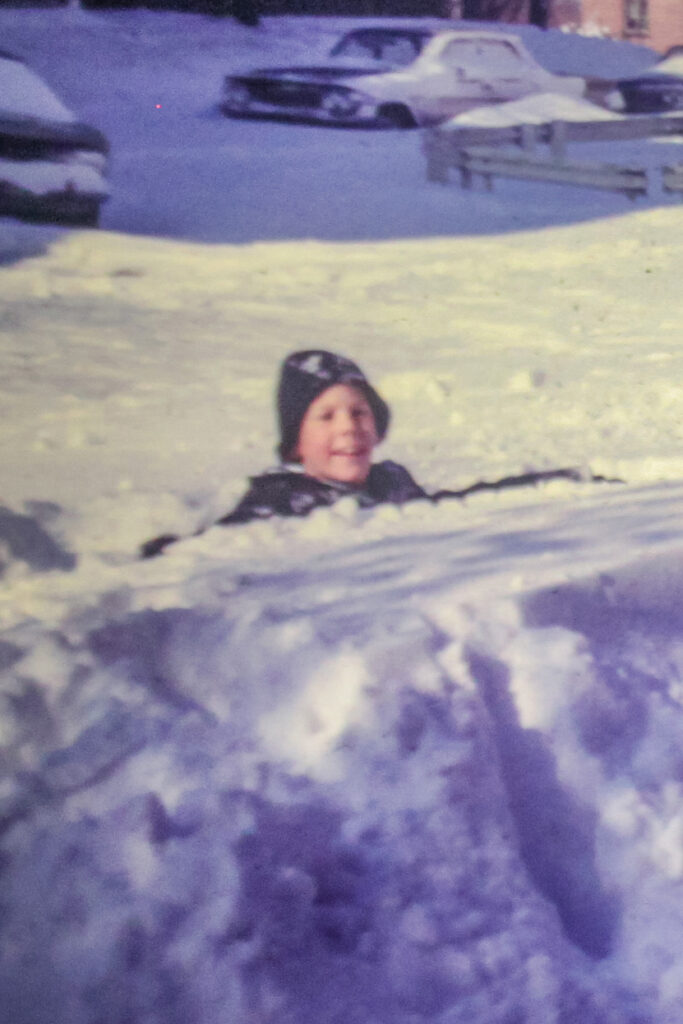

Having spent the majority of my youth in the Northeast, my mythical summer was actually a wintry snow day. The poet’s memories of climbing trees and skinned knees are my wistful memories of sledding, backyard skating rinks and drifts over my head.

When my parents relocated our family to western New England from North Carolina, I was five. I cried for 600 miles, wondering how I’d ever make friends in the North without the requisite language skills. I did make a lot of enduring relationships in those frosty years in the North, but the first was snow. Since moving back to North Carolina in 1988, I’ve missed snow like a childhood friend.

In New England, I learned how snow hides the jagged angles and softens the contours in our landscape and in our lives. Snow presents a bare canvas and the sense that all is clean and new and ready for our brushstroke—it’s a blank calendar page filled with promise and unfettered by practicality. After all, I was young and couldn’t be bothered with winter driving or shoveling any more than a trick-or-treating child might be concerned with notions of cavities or diabetes.

If such snowstorms didn’t occur every day, the anticipation would be constant. I would obsessively track a storm for days before its arrival. Some petered out; some held to the promise in that icy stillness that preceded it.

I learned that many northerners seem bound by a common grievance over snow, and winter storms were a rite of passage—abiding a storm in New England was currency. I endured both the Nor’easter in 1969 and the Blizzard of 1978. (I wasn’t there for the Storm of 1888, of course.)

To be clear, while I do love snow, I’m less impressed by winter. I don’t miss the gray, crusty piles that line parking lots and streets for months. I don’t miss the clean-up; I don’t miss hazardous commuting. I can’t stand the brine that coats guardrails, fender and shoes, and you can keep your interminable mud season.

Nor do I necessarily associate snow with Christmas, despite images on greeting cards or in Hallmark movies. I have experienced pitifully few white Christmases anywhere: my holidays have been barren and bare wherever I’ve been. Conversely, every snow day is a holiday to a child, Christmas or not.

But my move back southward effectively barred me from complaints. My southern friends quickly tired of my tales about the depths of northern snows; my friends in the north scoffed at my unabashed fondness for all things snowy.

“You love snow?” they’d say. “Feel free to come visit and exhume my car from a 12-foot snowbank.”

Upon relocating to Chapel Hill, N.C., I was immediately struck by southerners’ approach to winter precipitation, which was often humorous, if not misguided.

For example, weathermen in the South rarely use the word “snow” in forecasts: “Look out for a few flakes of that ‘white stuff…’”

After one storm, I actually heard a radio deejay suggest that grass or dirt provided better traction than icy streets, directing motorists to go off-road onto the shoulders or medians. Sadly, many drivers did just that.

In 1997, my town had one operational snowplow, which I watched get stuck on the shoulder of a major town road. The driver must have been listening to the deejays.

Here, the chance of a winter storm days away sends southerners to grocery stores in search of bread, milk, butter…and beer. I’m still not sure what the shopping list is for the storm-wary here, but it must involve French toast at every meal…and beer.

School districts in the South are notorious for cancelling class upon the mere mention of adverse winter weather and for several days afterwards, owing to black ice anywhere in this hemisphere.

If I was going to adjust to all of this, it would take patience and planning. After all, snow melts quickly here, so I endeavor to revisit all of those snowy rituals I fondly remembered with haste and impress them upon my own wife and children.

With as little as an inch of accumulation in the area, we would haunt the airwaves for school cancellations. We waited, chins in hands, and bore the closings in exotic North Carolina townships like Lizard Lick, Meat Camp and Horneytown. If our district’s name appeared, it wasn’t a reprieve; it was a call to action.

First, we’d harvest clean powder to make “snow cream.” Most say to start with a gallon of snow, then add 12 ounces of evaporated milk, vanilla extract and a ¾ cup of sugar. (Disclaimer: this was according to my southern wife’s snowy memories, as I never made snow cream in New England. Such are the concessions we make for marital bliss). It tastes a little like cotton candy…with ice cream headaches.

Snowball fights are compulsory here, if only because wet southern snow is infinitely packable—the stuff of concussions. Southerners generally don’t know firm powder. They’ve only known perfect snowball snow. Pearls before swine.

The last obligatory element in the yard is the snowman. Last because its creation strips all the snow from the lawn, so we take the photos for next year’s Christmas card prior to the decimation.

Many folks here remain close to home for sledding, opting for a 60-foot trip down an icy side street. Locals can remember when sledding hills were simply precipitous town roads, especially when that same one snowplow couldn’t clear the roads.

After one snowfall, I dutifully took my son out to get him used to driving in the snow. We found an unplowed parking lot where he tried unsuccessfully to skid in my Subaru. Now he’s living in New Haven and fending for himself. I’ve clearly failed as a father.

By late in the day, feeling as if I’d been inside a snow globe and shaken up good, I try to retreat into a snowy forest for a few magic moments in the gloaming. After all, much of snow is simply about that sacred silence—the rest note before the symphony of seasons begins again. But in these woods, there is only the hymn of breezes through the trees and my own breath; any other noise seems profane.

I pretend to empathize with my northern friends. But while some of them curse the snow every measurable inch, I find myself wanting to trade places and maybe they do too. We always want what we can’t have.

I’ve grown desperate, I must say. I once visited a mountain ski resort in western North Carolina to feel the bite of snow against my cheek, albeit blowing across a mountaintop from snowmaking equipment. And forget those snowy scenes in Lifetime movies that are incongruous with the summer flora in the background, and where steam from an actor’s breath is CGI.

Alas, I’ve become a hopeless snow snob—or, worse, a hopeful one. So, now as I face another winter, I’m buoyed only by the belief that I will see snow, a significant, lasting, glorious snow. And, just maybe, unicorns will become possible again.

A graduate of Dartmouth College, Randy B. Young worked in advertising in New England before relocating and working in communications for the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. N.C. Recently retired, he is a freelance writer and photographer.

More Stories

Foraging Around the Nutmeg State

Moving Up: Florida to Connecticut for Seasons, Schools and Safety

Listen Here! The Declining Art of Listening