New book chronicles New Haven club that drew Springsteen, Dylan, and the Rolling Stones

From the outside, little has changed at Toad’s Place over its 45 years as a downtown New Haven nightclub, presenting jazz, blues, reggae, pop, hip-hop, rap, and rock performers who range from those just starting out to Rock ’n’ Roll Hall of Famers.

The two-story venue on York Street still has its long green awning, red brick walls, and iconic logo of a spats-wearing, monocled amphibian dandy strutting his stuff. Though its hand-painted poster boards promoting upcoming shows have been replaced with electronic signage and its interior has been expanded and spiffed up, the basic vibe remains the same. Bands still rock, crowds still dance, and now multiple generations of music lovers can claim the club as a part of their forever-young history. It’s become as much a New Haven institution filled with tradition and memories as its next-door neighbor, Yale’s staid watering hole, Mory’s.

A new book —The Legendary Toad’s Place (Globe Pequot Press) — chronicles the club’s nearly half century of entertainment and drama, on stage and off, including performances by Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, The Rolling Stones, and Billy Joel.

Written by the club’s long-time owner Brian Phelps and former New Haven Register columnist Randall Beach, the book is an affectionate look back at the colorful life of a venue that has survived the test of many musical times.

As it enters its sixth decade, it has survived and flourished while other clubs have shuttered. It has weathered management dramas, out-maneuvered Yale for ownership of the building, and adapted to a dramatically changing music industry as well as ever-new musical tastes.

“After telling friends stories over the years, people would say I should really write a book before I start forgetting everything that occurred at the club over the decades,” says the New Haven born-Phelps, 67. He began at Toad’s in his early 20s in the ‘70s as manager of the club, before becoming partners with its original owner Mike Spoerndle, until taking over as full owner in the mid-‘90s.

“We tried to adapt to what was going on in the music world,” says Phelps, as one of reasons for the club’s longevity. He also says the club avoided being pigeon-holed as one particular type of nightspot. “We became a full music spectrum type of club, playing all different genres of music.”

Restaurant Beginnings

Toad’s (the “Place” in its name is usually dropped in conversation) began in 1975 not as a nightclub but as a casual restaurant in the building that once housed the burger joint, Hungry Charlie’s. Spoerndle — a graduate of the Culinary Institute of America, which was located in New Haven at the time — and two friends opened the new eatery in 1975.

But it wasn’t exactly packing them in, and that’s when Spoerndle figured what young people in this college town really wanted was a place to hang out, listen to music, dance — and drink. (At the time, the drinking age was 18.) The following year, Spoerndle bought out his partners and Phelps, who ran a karate studio above Cutler’s Record Store on Broadway, came in as manager for the re-configured space.

Early bookings featured such regional acts as the Simms Brothers, John Cafferty and Beaver Brown, the Scratch Band, the Helium Brothers, Roomful of Blues, Jake and the Family Jewels, Tower of Power, the Shaboo All-Stars, and folk singer Randy Burns. Because record-keeping was not comprehensive over the decades, Phelps can only estimate that Beaver Brown and Tower of Power played at Toad’s more than any other act.

Another reason for Toad’s success was its ability to book name bands, and that was due to the club’s association with rock promoter Jimmy Koplik, who was producing shows at the New Haven Coliseum and other arenas, stadiums, and festivals. Though New Haven was seen as a secondary market, the level of acts became significantly more high-profile because of Koplik’s association with the music industry and its artists.

“Jimmy was an extremely important part in our entire process over the years,” says Phelps.

Starting in the late ‘70s and into the ’80s, more and more acts that were famous — or about-to-be — filled Toad’s stage: Cyndi Lauper, Billy Idol, Blondie, The Red Hot Chili Peppers, Huey Lewis and the News, Stray Cats, Pat Benatar, Phoebe Snow, Michael Bolton, Phish, Rickie Lee Jones, David Cassidy, David Bowie, Ice Cube, Joe Cocker, U2, Beck, The Black-Eyed Peas, The Kinks, Patti Smith, Bon Jovi, Peter Frampton, Meatloaf, New Kids on the Block, Radiohead, Kanye West, The Go-Gos, Hanson, The B-52s, and scores of others.

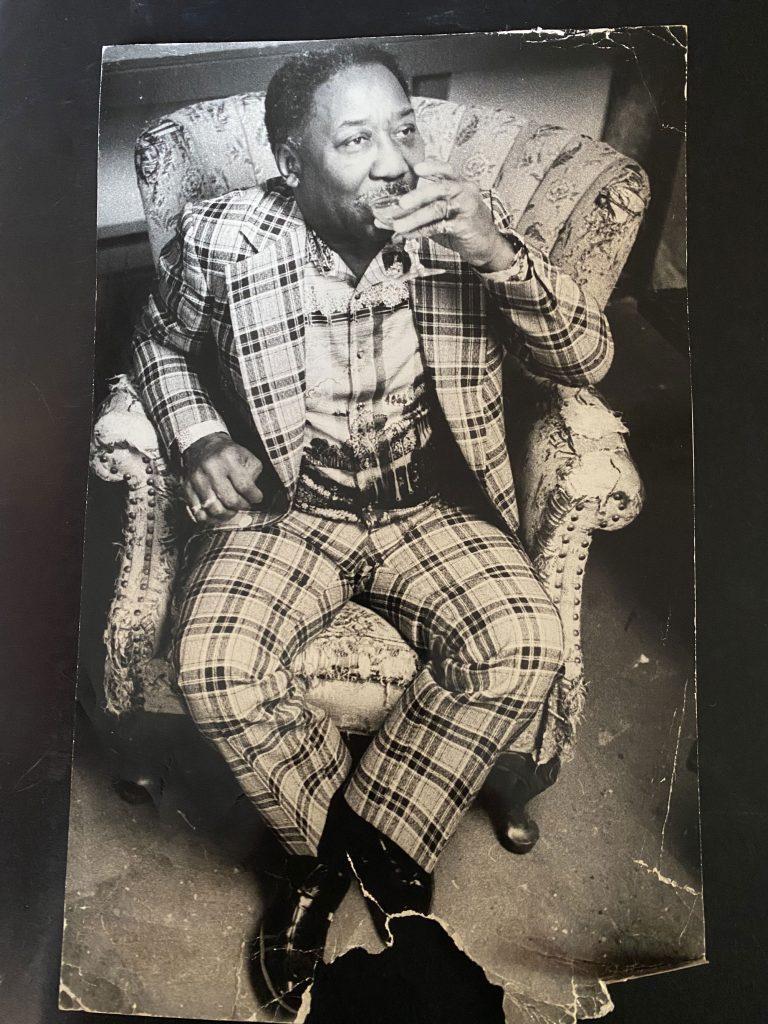

But classic legends of all musical styles also called Toad’s home: B.B. King, Count Basie, Bo Diddly, Woody Herman, Buddy Rich, Joan Baez, Little Richard, Dizzy Gillespie, Carl Perkins, Johnny Cash, Muddy Waters, Santana, and Herbie Hancock, among many others. The acts ranged from saloon singer Tom Waits to pop powerhouse Tom Jones, and iconoclastic figures such as Randy Newman, The Talking Heads, R.E.M., David Bowie, and The Ramones.

As Toad’s gained a national reputation, it became a must-stop for all touring acts. Even performers who filled stadiums sought the place out either as a place for an after-concert jam, such as Bruce Springsteen’s legendary performance there — or to try out new material in a surprise gig, such as The Rolling Stones, or a marathon show by Bob Dylan, or to record a live album, such as Billy Joel.

But there were a few misses along the way, too, such as Madonna because her asking price was too high; ditto for Kurt Cobain and Nirvana; when Paul McCartney backed out of a Yale Bowl gig following neighborhood protests against rock crowds, so went the expectation of the former Beatle playing Toad’s in a post-show jam with the band NRBQ, a McCartney favorite.

But most everyone else in the music biz — especially in the ‘80s and ‘90s, which was a period energized by MTV, the advent of CDs and personal listening devices, and big rock events — wanted to come party at the club.

That period was a special time, says Phelps. It was also before the full force of casinos competing for big name acts was felt, the fall of the New Haven Coliseum, and the presence of the College Street Music Hall, now the club’s most direct rival.

“Sometimes what’s playing at Toad’s now is a different genre of music than some older folks are used to,” he says. “Sometimes people say to me, ‘Why don’t you get the ‘good’ bands back?’ But what’s good to them isn’t good to someone else.”

Big Mike

Another immeasurable aspect of Toad’s appeal was the personality of its original owner, Mike Spoerndle, a teddy bear of a guy, whose warm smile and easy-going style made the club a welcoming venue for acts and audiences alike.

“Big Mike was the face of Toad’s, but also the heart and soul of the place,” says Beach, who adds that the partnership with Phelps — who focused on the club’s business management — complemented each other. “Brian was the guy who kept everything going, especially when Mike started to decline because of the addictions.”

Phelps became partners in the business with Spoerndle in the mid-80s. In 1998, Spoerndle sold his share of the club to Phelps, and Spoerndle died at the age of 59 of drug-related issues in 2011.

As for its relationship with its surrounding neighbor, Yale, Phelps says: “We have a great relationship with Yale now, though over the years, we’ve had our ups and downs.”

One conflict happened when the owner of the building — the club leased the property — put it up for sale and Yale offered hundreds of thousands of dollars over the assessed value, says Phelps. But as the lease owner, Spoerndle could buy it if Toad’s could match the offer — which it did.

Despite the stars, the music, and the money, managing Toad’s was not as easy as it looked,” says Phelps. “It’s tough and it’s rough. The stress really did a number on me. My teeth were ground to almost nothing, and I had to have crowns on every one of my teeth.”

Phelps says even he doesn’t know who many of the current hot bands are “so I have to do research and make calls and see what kind of business we would do.”

As for his future — and Toad’s, Phelps — who is sole owner of the club and its property — says, “I’ll probably be there for a while longer.”

And his most memorable night at the club? So many to choose from, he says. But when pressed, he says it was the August night in 1989 when The Rolling Stones — which had been playing stadiums — played at Toad’s. The band, which was preparing to go out on tour for the first time in eight years, wanted an out of the way place to try out its new songs and get their performance chops before they hit the stadiums. Admission to Toad’s that night was $3.01.

“We were in every newspaper in the country — and even in newspapers from other countries, including China.”

It’s been one eventful run, says Phelps. “When I think of it, presidents of the U.S. Supreme Court justices, famous actors, they’ve all been to Toad’s. That’s something.”

More Stories

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art: (Un)Settled Art Exhibition Moves Beyond Classic Landscapes

On Stage and Off, With Photographer James Meehan

FALL ARTS PREVIEW