At Home With Jacques Pépin

Turning 90, With Celebrations Nationwide

By Frank Rizzo

Call Jacques Pépin the quintessential American chef—and, after 50 years living in Madison, a full-fledged “Connecticut Yankee.”

Sure, he began his career more than 70 years ago as a culinary savant at some of the finest kitchens in Paris, later becoming the personal chef to French prime minister Charles de Gaulle. Yes, when he arrived in the U.S. in the late ‘50s, he worked at the most famous French restaurant in America: Le Pavillon. And, of course, his soft lilting accent is clearly français, n’est-ce pas?

Although Pépin literally wrote the book of kitchen techniques and whose high culinary standards are top chef, he is no snob.

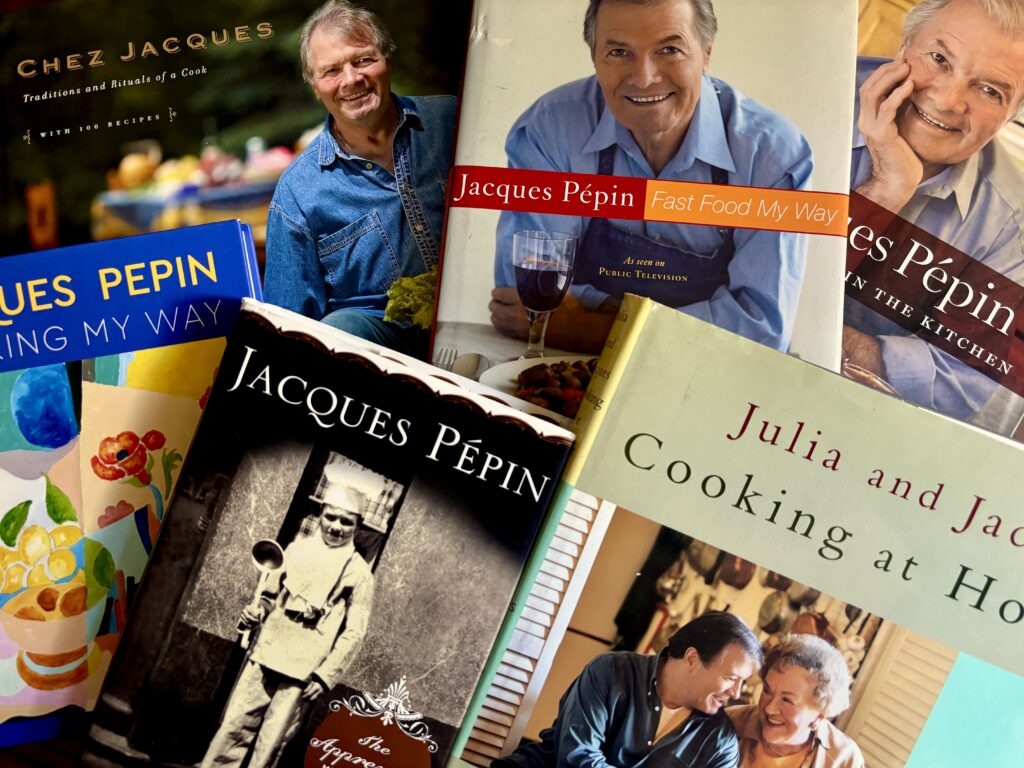

After all, in the ‘60s he turned down a position at John F. Kennedy’s White House to accept an offer from Howard Deering Johnson to elevate the food as his nationwide restaurants in the ‘60s. From the ‘70s on, Pépin became one of America’s most relatable cookbook authors, including ones whose titles reflect their home-cook accessibility: “Everyday Cooking,” “Quick and Simple Cooking” and “Fast Food My Way.” His many Emmy Award-winning television and on-line programs over the decades are also widely popular. (Two of his series included his daughter Claudine, now 57, and later his granddaughter Shorey, now 20.)

Pépin’s pals included such American culinary legends as James Beard, Craig Claiborne, Pierre Franey and Julia Child, who called him “the best chef in America.” In the late ‘90s, Child and Pépin partnered in writing “Julia and Jacques Cooking at Home,” and co-starred in its spin-off television series. Over his long career, Pépin earned 24 coveted James Beard Foundation Awards.

On a crisp summer day, I am at his Connecticut home primarily to talk about the master chef’s upcoming 90th birthday and the extraordinary events surrounding the occasion.

When I arrive, Pépin is perched on a stool and casually leaning on a large kitchen island, looking fit and trim in his navy polo shirt and gray slacks. A pegboard filled with shining copper pots and pans makes a golden backdrop for the interview. His black miniature poodle Gaston suddenly begins barking at the strange visitor.

“Arrêt!” says Pépin, and Gaston slinks back to his corner.

Pépin shows off his latest cookbook—his 35th—sitting on the island. “The Art of Jacques Pépin: A Life in Recipes and Paintings (Timeless Recipes and Signature Artworks of the Celebrated Chef)” includes some of his all-time favorite recipes along with some of his charming artwork. He adds that in the spring there also will be a 50th anniversary, combined edition of Pépin’s earlier two classic books of culinary techniques.

This fall marks the conclusion of the 90/90 celebrations: 90 fundraising dinners around the country in honor of his milestone birthday. The year-long salute ends on his actual birth date of December 18 at the Madison Beach Hotel. (There will also be special dinners on December 5 and 6 at the Ocean House in Watch Hill, R.I.)

Legendary American restaurants such as French Laundry and Restaurant Daniel were among those participating over the course of the year. In October, an eight-day event in Pépin’s honor will be held in Napa Valley, Calif. Fans of the culinary guru can also create their own fundraising dinner at their own homes by connecting on celebratejacques.org. Proceeds go to the Jacques Pépin Foundation, which supports community kitchen programs, culinary education for adults with barriers to employment and educational videos.

Always Learning

It’s been a long career and life and is still evolving—even after his 2017 profile when he was 82 in PBS’s “American Master” series on food legends. (Julia Child, Alice Waters and James Beard had their own separate documentaries.)

Mirroring Pépin’s recipe-filled memoir “The Apprentice; My Life in the Kitchen,” the documentary followed the chef’s life and culinary careers. He writes how, as a six-year-old son of a French Resistance fighter during World War II, he was sent for safety to the countryside to work on a farm in exchange for food.

After the war, young Pépin followed his mother into the kitchen where his family opened a restaurant, Le Pélican. There he found his calling and eventually moved to Paris at 16, working his way up the ladder in the feudal system of France’s most famous restaurants.

When Pépin came to America at 23, it was to be for a short visit. “I had a good job in France and I had everything I needed,” he says. “But you make a decision, and you think it’s just for a while, and then you make another decision, and it projects you to the next thing. That’s what life is all about. People would ask me, ‘Did you know you were going to be doing this or that?’ No.”

Pépin had a complex about not having a proper education. Living in New York City and working in restaurants, he also studied at Columbia University, thinking he might have a career in education. After he received his degree, he proposed a doctoral thesis on the history of French food in the context of French literature. It was rejected; he was told cuisine was “far too trivial for academic study.” Years late after establishing a culinary program at Boston University with Julia Child in 1989—Pépin received an honorary degree from Columbia in 2017. (B.U. gave him one in 2011.)

Pépin recalls with a wry smile his commencement speech to graduates, telling them, “Without an education, you’re likely to fall in the deadly danger of taking educated people seriously.”

Another Kind of Artist

Pépin’s interest in painting has worked its way into his culinary life with his artwork enlivening his books. Over the decades, he’s also created hand-drawn, special occasion menus, bordered with his whimsical and colorful drawings, all of which are bound and shelved in his study for handy reference and sweet memories.

Going upstairs, he shows off his studio where he paints. It’s a bright, airy room with a view of his backyard, garden and a small cottage with a large kitchen where he films his cooking episodes. There is a lawn expanse where he still plays with his friends the French game of petanque, a variant of boules. “I’m pretty good some days,” he says, “and on other days pretty bad.”

His wife Gloria died in 2020, after 54 years of marriage. In February, his best friend of nearly 70 years, Jean-Claude Szurdak, died at the age of 87.

Painting satisfies him in many ways, he says. “I get lost in painting like I get lost in cooking. Both are important things in my life.”

Pepin has a particular fondness for painting chickens. “It could be genetic,” he jokes. “I come from Bourg-en-Bresse, which has the greatest chickens in France: the best and the most expensive. And chicken was on the menu in six or seven ways, so it was already a big part of my cooking.”

Pépin raised chickens in his Madison backyard for a while, “but then the raccoons…,” he sighs with a shrug. (He admitted that his least favorite culinary task when he began his apprenticeship in kitchens was killing and plucking chickens.)

Painting and Cooking

How does his painting connect to his culinary skills?

“Often, I don’t really know exactly what I’m going to paint or where I am going with it,” he says. “Sometimes I would just want to do something abstract and, at some point, the painting takes a hold of me and I just react to that, putting a color here or a shape there.”

However, he points out, his culinary creations have to be standardized. Still, there are creative variables: “Because it’s summer and it’s more humid, or the chicken breasts are thicker or thinner, or I’m cooking with copper or aluminum, or gas or electricity, or if I’m in good mood or bad, things can change. In order for it to be the same, it has to be different and, like painting, that’s where adjusting and readjusting for taste comes in, sometimes when you’re not even realizing it.”

If he hadn’t become a chef, would he have been an artist?

“Yes, I guess. I could have moved in that direction. It satisfies me. But life was different then. My father was a cabinet maker and my mother was a cook. I could have been either a cook or a cabinet maker so the choice was easy for me. I never thought to be a doctor or lawyer. It never entered my mind. Now, kids can be 100 different things. But then life was simpler.”

How has the nature of starting out in the professional kitchens changed over the decades?

“Your job is to say, ‘Yes, chef’ because you’re not there to teach [famous chef] Thomas Keller how to cook. He has his way. You are there to learn, not to change things. I tell young chefs to find that job with that particular chef and just look at things through his eyes or her eyes and do it this way for a year or so, and then change and go with another chef. If you do that two, three or four times, you’ll have absorbed an enormous amount. Then you can filter it all through your own sense of taste.”

Frank Rizzo is a freelance journalist who writes for Variety, The New York Times, American Theatre, Connecticut Magazine, and other periodicals and outlets, including ShowRiz.com. He lives in New Haven and New York City.

Follow Frank at ShowRiz@Twitter.

More Stories

Moving Off To College

Over 50, Underestimated: The Grandfluencers Redefining Age on Social Media

Building Resilient Businesses: Strategies for Success