They wrote letters. They lobbied politicians. They conducted meetings.

They wrote letters. They lobbied politicians. They conducted meetings.

They argued with friends and family members. They went on hunger strikes. They held rallies.

They were jeered by opponents. They marched down the streets of Connecticut’s cities and towns. They were arrested.

Such were the actions of the Connecticut’s suffragists, who like many of their sisters in solidarity across the United States, spent decades demanding local, state and national legislation providing women the right to vote.

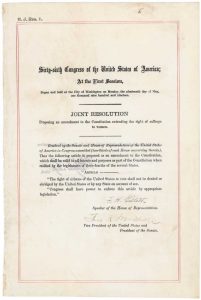

More than 100 years ago their hard-fought efforts paid off with passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution guaranteeing women voting rights. While the national movement was launched decades before in the 19th century by the women’s suffrage movement, it was action by the U.S. Congress in 1919 that helped proponents see that an end to the fight was near.

The start of the fight for women’s suffrage often traces its roots to the “Declaration of Sentiments” drawn up at the women’s rights conference in Seneca Falls, N.Y., in July 1848 with Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott as leaders. The first woman suffrage amendment was introduced in Congress in 1878 by California Sen. Aaron Sargent. It was defeated but later reintroduced each year, often as the Susan B. Anthony amendment, until it was passed in 1919.

Grassroots Beginnings

The Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA) was organized in Hartford in October 1869 by John Hooker and his wife, Isabella Beecher Hooker; her sister, and author, Harriet Beecher Stowe; another sister, Catharine E. Beecher; and Frances Ellen Burr.

The Connecticut Woman Suffrage Association (CWSA) was organized in Hartford in October 1869 by John Hooker and his wife, Isabella Beecher Hooker; her sister, and author, Harriet Beecher Stowe; another sister, Catharine E. Beecher; and Frances Ellen Burr.

Early CWSA efforts under the leadership of Isabella Beecher Hooker focused on letter writing and informational meetings. A more aggressive approach followed the election of Katharine Martha Houghton Hepburn (mother of the later famous actress) as head of CWSA in 1910.

Connecticut had its first suffrage parade in 1914 in Hartford attended by thousands of supporters.

Hepburn was followed by Katharine Ludington, portrait painter of Old Lyme, from 1918 until the organization was disbanded in 1921. Ludington went on to be a founding member of the League of Women Voters in the state.

The Connecticut Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage was holding its own rallies and meetings, including one at Hotel Taft in New Haven featuring statewide and national speakers.

On May 21, 1919 the U.S. House of Representatives passed the 19th Amendment, followed by the Senate, 56-25, two weeks later.

The role of the Constitution state in the constitutional fight for suffrage was marred by political control to the extent that the state finished in the race to ratification as the plus-one. With 36 states needed to reach the ¾ majority required to ratify, Connecticut finished No. 37 after Tennessee’s action in August 1920 made the amendment the law of the land.

The first three states to act were Wisconsin, Illinois and Michigan, all on June 10, 1919.

Political Opposition in Connecticut

In Connecticut, it was more a case of who was the holdout, rather than what was the hold up, in this state moving forward as a leader in ratification.

“Opposition was more political than ideological,” explains University of Connecticut political science professor Ronald C. Schurin.

The delay in action was in the hands of then-Gov. Marcus Holcomb, of Southington, who refused to call a special session of the General Assembly before its planned January 1921 session. Backing Holcomb was a small group of fellow Republicans known as the “Big Six.”

There was no bigger decision-maker for state political actions at the time than the powerful John Henry Roraback of Canaan. Roraback was the Republican State Central Committee Chairman from 1912 until his death in 1937 and Republicans dominated the state legislative political landscape, including control of the governor’s office.

“At that time, Connecticut was a very ‘Boss’-driven, dominated state. No Republican legislator would speak out in opposition to any party policy or practice in those days,” says Schurin, who has served as analyst and speech writer for the federal government.

From the perspectives of Roraback and Holcomb, the Republicans had plenty of voters and controlled state politics, so they had no need to add more, or even double, to the ranks by allowing women to vote.

In addition, Schurin points out that state political control was comprised of the many rural and farm communities of the state. Roraback was from a family of lawyers who dominated Litchfield County. Adding women might swell the voting ranks, thus the political power of the cities.

“During the Roraback years on into the shift to the John Bailey-led Democrats [Bailey was elected chairman of Democratic State Central Committee in 1946, and later head of the Democratic National Committee] was a time when legislators very rarely broke with the party line and leaders,” says Schurin.

Despite appearances, Schurin says Roraback was known also as a good listener within party ranks and led more in step with others rather than in a dictatorial style.

Ideological opposition to women’s voting rights largely centered around family and social issues, including child labor laws, religion and Prohibition. The Connecticut Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage argued that much of the social progress gained by women in prior decades created additional burdens for women and that the responsibility for voting only added to these burdens.

After Tennessee’s action in August 1920, Holcomb finally called for a special session on Sept. 14, for the limited purpose of setting up a voting process for women in the 1920 presidential race. The legislators took matters in their own hands and pushed for ratification of the 19th Amendment. Among some concern the step could be illegal, the General Assembly met again in a second special session to verify the vote.

Women Ascend to Elected Offices

The 1920 presidential election, the first in which women could vote, was won by U.S. Sen. Warren G. Harding, a Republican, who defeated Gov. James M. Cox, a Democrat. Both men were from Ohio.

That year Connecticut elected its first women to the General Assembly: Emily Sophie Brown of Naugatuck and Lillian S. Frink of Canterbury, both Republicans; Helen A. Jewett of Tolland, a Democrat; and Grace I. Edwards of New Hartford, an Independent.

The first woman in the State Senate came four years later when Alice Merritt, a Hartford Republican, was elected.

Connecticut was in the national political spotlight in 1970 when Ella T. Grasso, a Democrat from Windsor Locks, became the first woman in the country elected in her own right (not succeeding a husband). Grasso had a storied leadership until she resigned after being diagnosed with ovarian cancer in December 1980.

One twist to Roraback’s political role in Connecticut’s legacy is the feminist and civil rights legacy of his own great-niece, Catherine “Katie” Roraback. She was the daughter of the Rev. Albert E. Roraback, and granddaughter of Alberto T. Roraback, a prominent politician from North Canaan and Chief Justice of the State Supreme Court.

Catherine Roraback, who died in 2007, was inducted into the Connecticut Women’s Hall of Fame. She was the only woman in her Yale Law School class of 1948. Among her legal achievements in a 50-year career, she successfully defended a case against Estelle Griswold and Dr. C. Lee Buxton, who were arrested for opening a New Haven birth control clinic. Connecticut had one of the strictest birth control laws in the nation, which she was able to successfully challenge in Griswold vs. Connecticut.

With a presidential election on the horizon, current Secretary of State Denise W. Merrill had hoped for a year-long celebration leading up to the November 2020 election until all plans for public events were derailed by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Merrill and Lt. Gov. Susan Bysiewicz joined with Annie Lamont, wife of Gov. Ned Lamont, to co-chair the Connecticut Women’s Centennial Suffrage Commission. In January the commission issued a report, “Fifty Years of Women Candidates,” studying women in statewide elected office.

Among other conclusions, the report found that when women run for office, they win at the same rate as men.

“The hope,” says Merrill, “is that this report will start a conversation about how far we’ve come in terms of women’s representation, where we are now, and what’s left to be done. Even today, only 35 percent of candidates in Connecticut are women – we need to change that. So, to those women contemplating a first run for office, or a second or a third or a fourth, consider this your official ask: run for office.”

More Stories

Haunted Apples and Bewitched Beer

Gayle King speaks to Dennis House

Everybody Remembers Their First Outdoor Concert