“My name is Ranger Andy and I’ve traveled all around.”

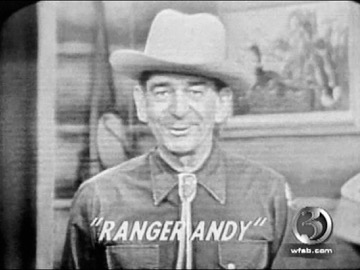

In the late 1950s and through the ’60s, those words beckoned kids growing up in Connecticut and southern New England to watch a banjo-playing troubadour in a ranger hat for a half-hour TV show that in its heyday was the #1 children’s program in Hartford. Ranger Andy aired weekdays from 4 to 4:30 on WTIC-Channel 3.

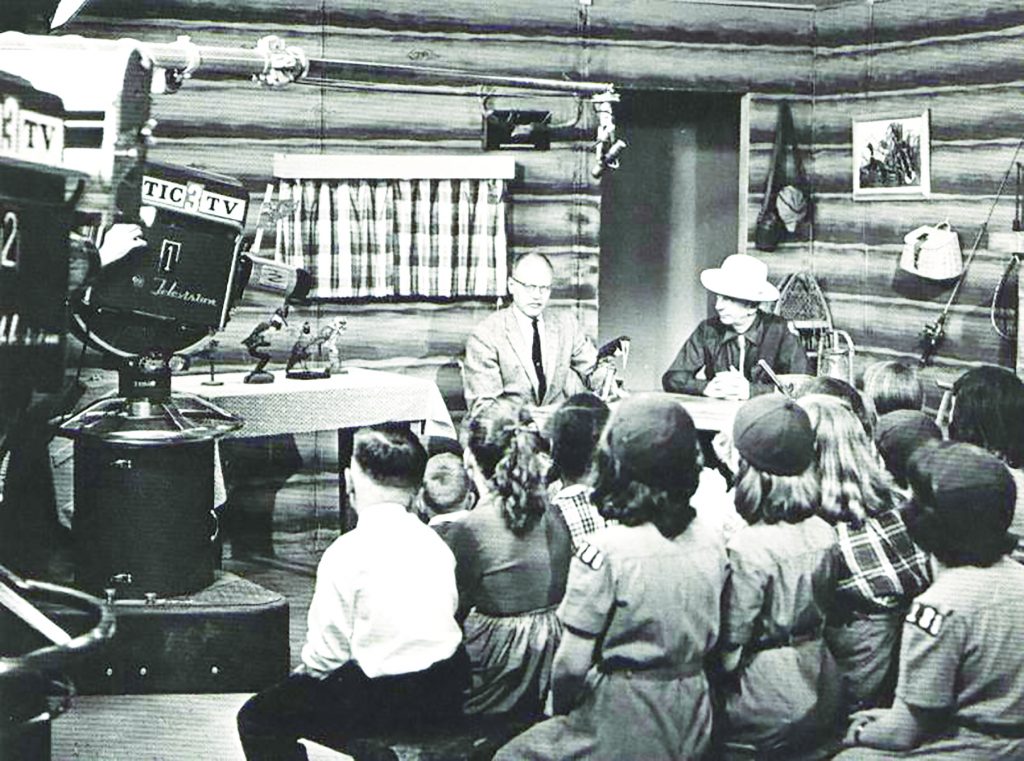

More exciting than watching the show? Appearing on it, a lifetime memory for thousands of youngsters, as each day’s program required at least 30 kids to join Ranger Andy on the set for songs and games. Many kids dressed in their Cub Scout or Brownie uniforms, eager for their moment in the spotlight. Birthday boys and girls and their party guests often appeared with Andy.

Pat Reno worked in the television station’s promotion department. One of her duties was mailing out tickets for the show. “All the mothers would come into the studio while their children were on the show,” recalls Reno, retired and living in Farmington.

During the show’s run, from 1957 to 1968, television was coming of age. It wasn’t like TV today with virtually unlimited channels. If you lived in Southern New England, you could only get three channels: WNHC, Channel 8, in New Haven; WJAR, Channel 10, in Providence; and WTIC, Channel 3, in Hartford.

It was a time when a television set, arriving into your home, felt like a new piece of furniture. With the most powerful signal, Channel 3 was king, its programs from downtown Hartford reaching beyond New Haven and north to Springfield.

The show debuted from television studios on the sixth floor of the Travelers Insurance Company’s Grove Street building across from Travelers Tower, the seventh tallest building in the world when built in 1919. In 1962, WTIC, Channel 3, moved to nearby Constitution Plaza, a model urban renewal project that replaced Front Street, a neighborhood of 18th- and 19th- century buildings, housing mostly Italian immigrants. Broadcast House, one of the first sleek new buildings to anchor the plaza, was the TV station’s new home.

Andy’s Origins

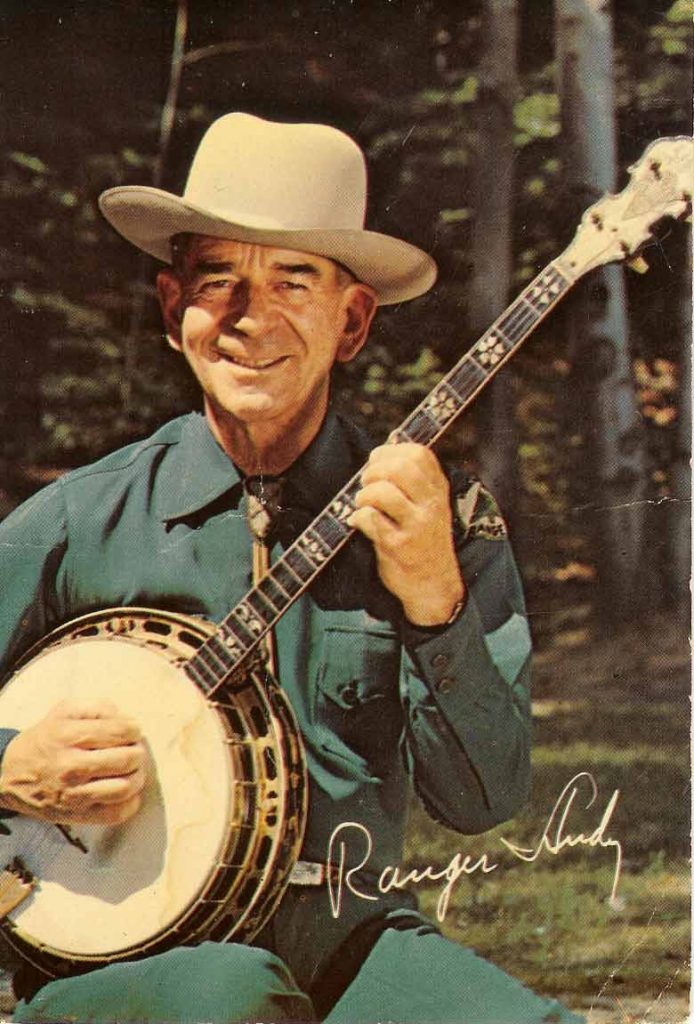

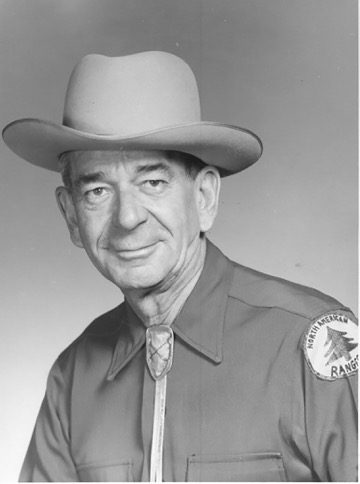

The show starred Orville Andrews, an actor and singer who had created the character, Ranger Andy, on a NBC Perry Como Show Christmas special in 1956, performing songs on his banjo and delighting kids.

After the first Ranger Andy show aired in Hartford, shortly after the station went on the air in 1957, Andrews continued to develop the character. He wore a green forest ranger uniform and performed on a set designed to look like a ranger station.

At the start of the program, Ranger Andy would stand in the doorway of the set, replicating the interior of a log cabin, and exclaim: “Let’s see who’s coming up the trail.” That was the cue for 30 or more youngsters to file in and take their places on wooden benches, where they would join him for songs, games (like Simon Says), and riddles and jokes.

Being live TV, sometimes the unexpected happened. One time, a guest from a nature center appeared on the show with a live rabbit. That day, a big Christmas tree stood on the set and a wreath hung over a fake fireplace. Suddenly, the rabbit leaped out of the guest’s arms, dove onto the tree, and pulled it down. Ornaments smashed and kids screamed.

“We went dark and to commercial while we regained our composure,” recalls one of the show’s directors, Dan McAuliffe, now of Venice, Florida.

In between the live segments, taped excerpts from programs, such as The Laurel and Hardy Show, ran. Commercials, often done live, were geared to children, with sponsors including Hostess Cupcakes (with Ranger Andy’s young guests getting free cupcakes) and potato chip companies.

Ranger Andy wasn’t the only show in town. Flippy the Clown, starring Ivor Hugh, entertained kids. So did The Hap Richards Show, which starred Floyd Richards, a WTIC-AM radio announcer, who transitioned to television. Indeed, stations in every major city in the nation aired locally-produced children’s shows. They had to, according to the Federal Communications Commission, which more heavily regulated TV broadcasting in its early days. One condition for a station license was an agreement to provide a certain portion of the broadcast day with children’s programming, says Ellen Seiter, a professor of cinema and media studies at the USC School of Cinematic Arts.

“There was a great deal of concern in the early days of television that its presence in the household would disrupt the domestic routine,” says Seiter. “So early morning and late afternoon programming was scheduled for children to allow the presumed housewife to make meals, et cetera.”

But Ranger Andy reigned, not only because of Channel 3’s reach, but also because the Travelers, which owned WTIC, invested heavily in staff and programming.

“It was an institution,” says Jim Stewart, of Berlin, who was a director and producer of the show. “To go back to school the next day and say, ‘I was on the Ranger Andy show.’ That was big stuff.”

One of those kids was future novelist Wally Lamb, who was on the show in 1959 or 1960 as a fourth- or fifth-grader.

“I was really excited,” recalls Lamb, who took a long bus ride from his hometown, Norwich, to Hartford, with his Cub Scout troop for the TV appearance. “I remember calling all my relatives the evening before. It seemed miraculous.”

The event left such an impression on him that he wrote a novel, “Wishin’ and Hopin,’” which features a fifth-grade narrator named Felix Funicello, who appears on the show, and tells a sexist dirty joke live before a shocked Ranger Andy. The show immediately cuts to commercial. Though fictional and the stuff of urban legend, Lamb says he’s talked to others who appeared on the show where a young boy actually told such a joke.

Like thousands of his generation, growing up in Connecticut, Lamb remembers the Ranger Andy songs. During a phone interview, Lamb breaks into song to prove his point: “My name is Ranger Andy and I traveled all around/And I will tell you many things about the things I found/I’ll sing about the mysteries of animals galore/And I hope to tell you many things you never learned before/Come along. Sing a song…”

Many other local baby boomers who grew up here can recite the lyrics to Ranger Andy tunes like “The Song That Never Ends” (“Chingdum diddle and a hi-dee-dee/the song that never ends”) and “You’ll Find It in the Bible” (“You’ll find it in the Bible/You’ll find it in the Bible/You’ll find it in the Bible ’cause you know it’s there.”) Or the closer, “It’s Great to Be a Ranger.”

Beetle Juice

For Orville Andrews, Ranger Andy was a job. He would drive his Volkswagen Beetle in from his northwestern Connecticut home in Kent to prepare for the show, recalls Stewart.

Born and raised on a Nebraska farm, Andrews went to the University of Nebraska to study agriculture. He might have joined the ranks of actual forest rangers, but he discovered acting and went on to graduate school at Nebraska, studying music and dramatics. To pay his way, he played banjo in dance bands in Nebraska and Colorado. He later moved to Hollywood where he appeared in a few movies, as well as on radio as a comedy singer. He also created some of the best-known radio jingles of the late 1930s and 1940s, including one for Bromo Seltzer, according to his obituary in The Hartford Courant. He died after a brief illness in 1968 at the age of 63.

Parents and teachers often marveled at how Andrews could hold the attention of 30 or more excited boys and girls. His answer: “Treat them like adults,” he was quoted as saying in his Courant obituary.

After Andrews’ death, several announcers rotated as host of the show, including WTIC-AM radio personality Arnold Dean, who died in 2012 at the age of 82. The permanent job went to Jim Thompson, who had sung in nightclubs and performed in light operas. The show title changed to The Ranger Station, with Thompson, who now lives in Stratford, hosting under his own name.

Thompson’s show lasted five years. In 1973, Traveler’s sold the TV station to Post-Newsweek Stations, Inc., and in January 1974 the call letters changed to WFSB, which stood for Frederick S. Beebee, then president of Post-Newsweek. Many who worked on the Ranger Andy show still meet annually as part of a WTIC Alumni group.

“It was a very special place to work, [before the sale],” says Stewart.

Leonard Felson, a regular contributor to Seasons, is a magazine writer whose passion for local history began at a young age. For more about him and his work, see www.leonardfelson.com.

Photography Courtesy of WTIC Alumni Association

More Stories

Haunted Apples and Bewitched Beer

Gayle King speaks to Dennis House

Everybody Remembers Their First Outdoor Concert